Ќumugweʼ (Komokwa)

The Wedding of Ќumugweʼ and Tlakwakilayokwa, oil on linen, 59" x 56" by Richard Walking Buffalo* Tylman

*) Name 'Walking Buffalo' (Mostos Takohtêw) was bestowed upon Richard Tylman by Master of Ceremonies Okimaw Piyesiw Awasis (Cree chief Thunderchild) at the Tsawwassen Nehiyaw Matot'sân on the Tsawwassen Lands Reserve in Vancouver on 19 May 2018.

(close pop-up)

Sea-God and Copper King, Ќumugweʼ is the most powerful deity in the mythology of Indigenous nations of the Pacific Northwest. His other name is Tlakwagila (spelled L!ā´qwag·īla in Boas) meaning Copper Maker, or the Rich One, in reference to his enormous wealth.

Ќumugweʼ rules over the oceans and all life teeming within. His undersea house is guarded by supernatural monsters and has sea-lions as house posts; it is full of treasures. Some say Ќumugweʼ, pronounced ['koo-moo-gwé], also known as Komokwa, Komokoa, Qumugwe, or Goomokwey, is the Spirit of the Giant Octopus (pigment-changing Enteroctopus dofleini of the North Pacific: with three hearts, strong circular suckers (pictured), and blue, copper-based blood. Octopus is the world's most intelligent invertebrate capable of recognizing a person coming in contact with it. But Ќumugweʼ is an anthropomorphic being; human rather than animal-like in appearance and exhibiting human qualities. He is the equivalent of the Olympian god Poseidon (Neptune) from classical Antiquity.

As the Lord of the Seas, and Chief of the undersea world, Ќumugweʼ (the Bringer of Wealth) commands the lives of the most significant sea creatures, including apex predators such as whales, killer whales, seals, sea lions, but also the running of salmon, and the spawn of herring; vital to Indigenous economies and essential for the health and wellbeing of all coastal peoples. His head is said to be so big that it looks like an island. Ќumugweʼ is portrayed by Tylman as emerging from the magnificent kelp forests.

Ќumugweʼ is sometimes incorrectly referred to as Qaniqilak. According to reliable sources* Ǭaniqilak means Flying-on-Wings. Ќumugweʼ does not have wings. Anthropologist Franz Boas spelled Qaniqilak as Q!ā´nēqēɛlaku. He called him the Most-Beautiful-One, which was a translation provided by George Hunt from the word Ëx·ɛEqâ´laġEmaɛē. (See pop-up)

Tlakwakilayokwa

The most fascinating part of Ќumugwe's myth concerns the presence of Talio (Tlakwakilayokwa, also called Kominaga), a human transformed by Ќumugwe' into his own likeness. Tlakwakilayokwa was a high-ranking female also known by an illustrious title of Born to be Copper Maker Woman. According to legend, she was given away as bride by her own father, a hereditary chief. Be willing or not, she was married to a supernatural being to bring prosperity to her people, and to become a supernatural being herself. Her persona is easily recognizable, because her face is decorated in a pattern similar to his by the carvers of Kwakwaka'wakw and the Nuxálk nations.

In Tylman's painting Tlakwakilayokwa wears the sea-otter pelt over her shoulders, similar to Naida in the film made by Curtis.* However, to signify her innocence and virtue, but also vulnerability and powerlessness in a matter of gratuitous gift-giving rituals, she is depicted as not wearing anything underneath. (see: Curtis' 1914 Film Description* pop-up)

* See In the Land of the Head Hunters (also known as) In the Land of the War Canoes (1914); via Wikimedia Commons. Fictionalized silent film, written and directed by Edward S. Curtis. Running time 65 min. Seattle Film Co, USA. Featuring Maggie Frank as Naida (uncredited) cast along 2 other women (Sorceress, and Na'nalalal Dancer), Vancouver Island, British Columbia. See also: new Digital Restoration* by UCLA Film & Television Archive in collaboration with Milestone film & video, 2013. YouTube 1:11 min trailer. (close pop-up)

|

Background mythos

Ќumugweʼ (the Copper-Maker), also called L!ā´qwag·īla by Boas in reference to his wealth, lives in a mythical residence known as Monster Receptacle which is guarded by living posts who speak with contradictory voices. In the book by Boas the scene is described as follows:

|

|

| | Mask of Kumugwe, MoA |

|

| |

All the rafters of the house were sea-lions; and also the four posts, and the cross-beam on top of the posts had sea-lions at each end; and the posts in the rear of the house were the same; and the two long beams of the house also had sea-lions at the ends; and the house had four platforms on its floor.

Two speaking-posts stood one on each side of the door... the one on the right-hand side of the door spoke, and said: "Attack this stranger who has come into your house, Copper-Maker." Thus he said. Then the one on the left-hand side of the door also spoke, and said: "Treat him well. He came to get a supernatural treasure from you, chief." Then he stopped speaking, and the attendant spoke and said: "This is the house of Chief Copper-Maker, whom you call Wealthy at the place where you come from." All the sea-monsters in the world under the sea were his servants.

— Franz Boas and George Hunt, 1906* pop-up — Franz Boas and George Hunt, 1906* pop-up

* Source: Franz Boas, George Hunt (1906), Kwakiutl Texts – Second series. The Jesup North Pacific Expedition; New York, Vol. X, Part 1, pp. 62, 63 (72, 73 in PDF). American Museum of Natural History, Digital Repository; New York, NY.

(close pop-up) |

|

In ancient carvings by aboriginal artists, the head of Ќumugweʼ is large, rounded and heavy, with wide, thick lips, and a short, broad nose characterized by flared, elongated nostrils. He has visible gill arches, and in many representations the most prominent circular suckers, with muscular suction cups surrounding his mouth. In contrast to the eyes of the terrestrial creatures, his eyes are painted to look more aquatic, as with deep-diving adaptations.

Ancestry

In crest art Ќumugweʼ wears riches of the sea as his headdress including starfish and other marine creatures such as loon, sculpin, octopus and orca. He might be seen with the sea-urchins as earrings; his crown, reminiscent of a scallop shell.

|

|

| | Mask of Kumugwe, MoA |

|

According to one legend Ќumugweʼ commands high rising tides and whirlpools. His house is made of copper. The motif of Coppers – shaped as Shields and used as currency of the highest denomination – is frequently incorporated as His symbol on poles. He is also known as Protector of the Seals, thus confirming the special status reserved for these animals. His undersea house shared with Talio is full of rare treasures guarded by the Supernatural Crane called Khenkho – recognizable by his long, narrow beak. Khenkho resembles both the mythical Cannibal Bird Huxwhukw, and Cannibal Raven. (Selected Sources* pop-up)

1. Canadian Museum of History, 'Copper Shields.' From Haida Art by George MacDonald. Douglas & McIntyre, 1996, ISBN 0-295-97561-X.

2. Cheryl Shearar (2008), Understanding Northwest Coast Art. Douglas McIntyre (D M Publishers), p. 94. ISBN 1926706161.

3. Alan Dundes (2003), Parsing Through Customs. Univ. of Wisconsin Press, p.55. ISBN 0299112640. Google Books.

4. Audrey Hawthorn, (1994), Kwakiutl Art. University of Washington Press, Seattle, pp. 28, 185. ISBN 0-295-96640-8.

5. Khenkho Explorations (2004), 'About Us.' Names of mythological creatures. Internet Archive Wayback Machine capture.

(close pop-up) |

Painting development process

| Richard Tylman, first watercolour

sketch for "Ḱumugwe' with Wife"

dated Spring Solstice' 1996 |

The very first concept sketch for the double portrait of 'Ќumugweʼ and Tlakwakilayokwa’s Wedding' was produced as far back as March equinox 1996. The small watercolour study visualized the interaction between spirit and human worlds. Initially, the idea for a large oil painting was put to the side while new reference materials for all aspects of their mythical lives together were being collected. It was a thematic and formal departure from representations of individual dieties in this series.

The actual oil painting was initiated almost 20 years later. It became the fourth painting in the series of Indigenous gods. Artist inspiration included Native carvings spanning over a hundred years, ancient texts and frontier photographs of wedding ceremonies, Bridal Groups, and (now already famous) portraits of Native women taken by Curtis and published in The North American Indian.

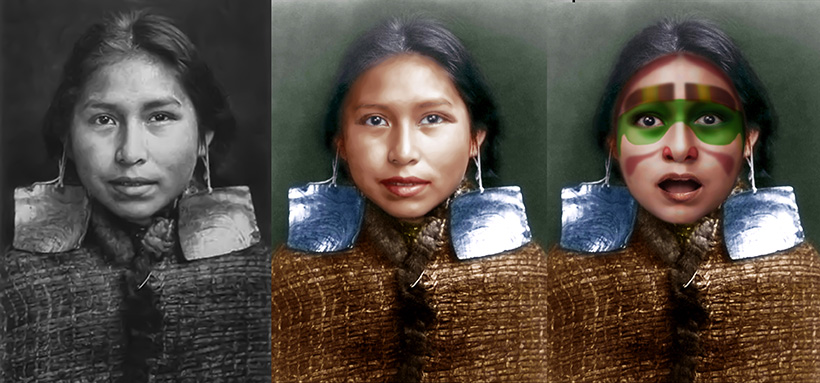

Margaret Wilson Frank by Edward Curtis (1914), first colorized by hand and than reimagined by Tylman as the Spirit Bride, overcome by intense feelings.

Tlakwakilayokwa’s likeness is inspired by the iconic portrait of an actual real-life actress, Margaret Wilson Frank, cast in the role of the Kwaqiutl bride named Naida* in the fictionalized silent film made by Curtis in 1914. It was the first feature film made in British Columbia and the oldest surviving feature film made in Canada, acted entirely by native people. (see Archival Restoration* pop-up)

Edward S. Curtis left behind an enormous photographic legacy, made possible by a generous grant from J. P. Morgan ($75,000 for 5 years of fieldwork, or the equivalent of more than $350,000 annually in today’s dollars), which led to the publication of twenty volumes of The North American Indian * mega encyclopedia between 1907 and 1930, featuring 2,228 glass plate photographs (see Digital 2003 Edition hosted by NU Library* pop-up). * mega encyclopedia between 1907 and 1930, featuring 2,228 glass plate photographs (see Digital 2003 Edition hosted by NU Library* pop-up).

Note: Colorization of Margaret Wilson's photograph was first introduced by Tylman before the AI on Facebook, September 10, 2018.*

|

| See also: |  | |

|